Here we discuss a project that was done in the Education Track during the Wolfram Summer School 2017

Introduction and Abstract

For many years, Logo and its programmable turtle have served as an entry point to computation for programmers around the world. While modern languages like the Wolfram Language have developed into true "knowledge machines", current turtle-based languages like NetLogo are still quite powerful when a problem can be described using agent-based thinking. In this project, we hoped to explore what agent-based thinking looks like in the Wolfram Language.

Much of the work we did is much less of a software-engineering project (e.g. lots of code) and more of a language-design project (e.g. short, readable code). Because this project meant to make extensive use of Dynamic and Manipulate, I spent much of the time examining these and the accompanying ControlTypes. My first attempts to create a simple MABM (Multi-Agent Based Modeling) framework (e.g. many-turtled-framework), focused on the idea of "porting" various turtle-ideas into Mathematica code. However, this very much against the functional paradigm, so we instead tried to make use of a Locator with Dynamic position as basis for a Turtle (with the added benefit of draggable turtles!). While this served its purpose, it didn't provide the "abm" kind of Manipulate that we were looking for.

The outcome of this work is a controller/Manipulate we call abmManipulate. abmManipulate takes just two parameters: some sort of setup method and a list of action-condition pairs. The setup method is provided by the user in order to spawn turtles with custom properties, positions, headings, etc. The action-condition pairs are written as pure functions, giving total control over any and all turtles to the user. Within each pair, action is a function which operates on a single turtle and can be written in such a way such that any generic turtle task can be represented. The condition element, is a parallel of the ask structure in ABM languages: it determines which turtles will be "asked" to perform the action. Using this new framework, we developed three example models, all of which are runnable. In essence, we've enabled a new kind of complexity-experiment in Mathematica: observing the emergence of global properties (world state) from the easy-to-understand and simple rule sets of turtles.

While the main part of deciding how to model a turtle in WL has been prototyped and proven, the implementation we have here left us with serious questions about efficiency and readability. While we tried to provide a modest amount of syntactic sugar, the syntax in declaring the various functions necessary to call abmManipulate leaves something to be desired.

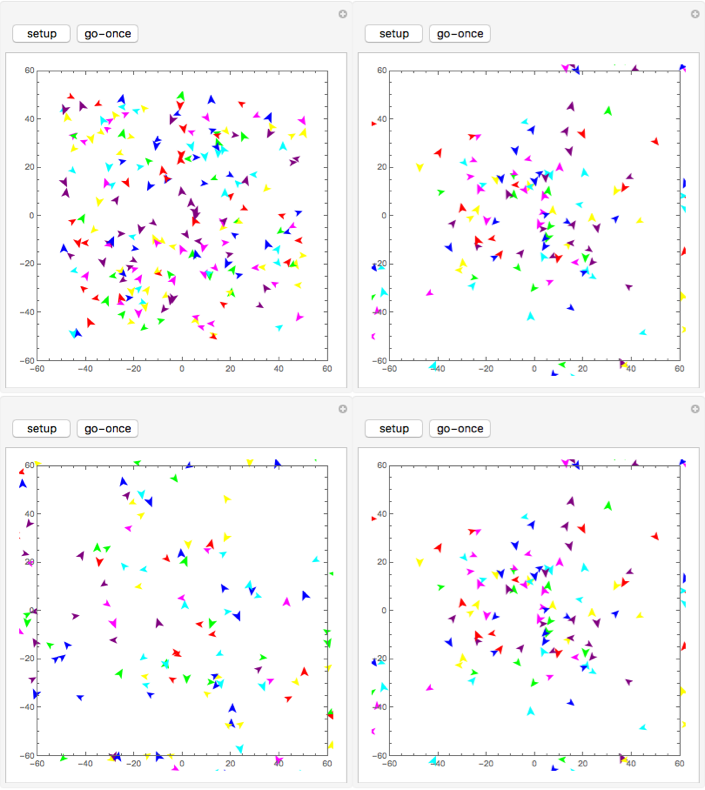

Screenshots (from Heroes and Cowards)

The Framework: abmManipulate[]

The main result of this work is a new function, abmManipulate. In essence, abmManipulate is simply an agent-based wrapper for Manipulate. The main difference is that while in Manipulate you often specify certain variables to be manipulated by ControlTypes, abmManipulate takes in functions that define the agents and agent-behavior to be modeled.

abmManipulate has two parameters: a setup method and a list of action-condition pairs.

The setup method should be a function that does any sort of customization on the turtles that the user needs to setup the state of the world. The crucial part of this function is the adding of the Turtles to the global world state.

But wait! What's the Turtle construct? Actually, the Turtle is simply an Association. In this way, you can not only add an arbitrary number of properties (and if you're really cool tasks), but you can also easily access any of these properties by using normal association Part syntax: aTurtle["position"]. These turtles get rendered to the world by being processed as Locators. We create a two-way binding using Dynamic between this Locator and the Turtle it represents so that any manipulation of the Locator updates the Turtle's properties. A Turtle has certain default properties: a "who" number which is simply the index of the turtle in the global world, a "position" which is an {x,y} coordinate pair which is self-explanatory, "heading" which is an angle (in radians) relative to the positive x-axis which corresponds to the direction in which the turtle is heading, and "shape" which is the marker used to represent the turtle (a Graphics object).

Turtles are created via the crt[n] method, which returns a list of n-Turtles. By default, the turtles are assigned random positions, random headings, and a classic turtle shape with a random coloring.

In the setup method that is passed to abmManipulate, the user uses crt[n] as a way of creating turtles to add to the global turtles list. Then the user can apply custom augmentations to all the turtles generated by crt[n] by performing a simple Join on Associations. In this manner, to apply custom properties to a turtle, one need only Join the Turtle with a new Association that contains the desired key-value pairs for properties the user would like to add. This has the added benefit of also allowing the user to override the randomly generated properties of the turtles by simply using the original Turtle as the first argument to the Join. An example is below:

setup := $Turtles = With[{n = 200,type := RandomChoice[{"hero","coward"}]},

Join[#, <|

"behavior"->Evaluate[type],

"friend"->RandomInteger[{1,n}],

"enemy"->RandomInteger[{1,n}]|>]& /@ crt[n]

]

In the above example, we create 200 turtles. We then add three custom properties: "behavior", "friend", and "enemy". We could easily modify the above code to re-specify a particular position for all of the turtles as well:

setup := $Turtles = With[{n = 200,type := RandomChoice[{"hero","coward"}]},

Join[#, <|

"behavior"->Evaluate[type],

"friend"->RandomInteger[{1,n}],

"enemy"->RandomInteger[{1,n}],

"position"->{0,0}

|>]& /@ crt[n]

]

Now, all of the turtles will begin at the origin. Because of the ordering of its parameters, Join these two associations will result in the original assignment of position being overwritten.

The action-condition pairs are simply a list of associations of the form: <|"action" -> someAction, "condition" -> someCondition|>.

Here, someAction is a pure function that is fed a single argument, the who-number of a turtle to perform an action. someCondition is a PatternTest that is applied to each of the turtles in the world and returns a List of turtles that meet the condition. Two examples are below:

sampleCondition := AllTrue[#["position"], 0 <= # <= 50 & ] &

sampleAction := Function[self,

$Turtles[[self, "position"]] = (0.95 $Turtles[[self, "position"]]) + (0.05 $Turtles[[RandomInteger[{1, 200}], "position"]])

]

Now that we have our three arguments, we can finally call our new function: abmManipulate[setup, {<|"action" -> sampleAction, "condition" -> sampleCondition|>}]

To ask different groups of turtles to do different things, one need only add new action-condition associations to the second argument:

abmManipulate[setup, {<|"action" -> sampleAction1,

"condition" -> sampleCondition1|>,

<|"action" -> sampleAction2, "condition" -> sampleCondition2|>}]

It should be noted that there was some inherent tension in this work. While Turtle-based logic is inherently state based (i.e. a turtle has a position and a heading at the very least), a purely functional language minimizes the concept of state. Luckily, WL presents an impure functional language, so we take advantage of this to create the idea of a Turtle controller. However, using a global $Turtles structure causes serious issues with cross-notebook compatibility. In addition, while we originally intended this to be an accessible structure to enable anybody to do "turtle-based" thinking, it's really more of a tool for ABM-ers who are interested in using WL. This is particularly true in the actions that we ask turtles to perform. In a more Logo-ish environment, you don't "ask a turtle to sets its position." Instead, you "you ask the turtle to move towards a position." The difference is slight, but the latter is what Seymour Papert called "body syntonic" because you can "play turtle." That's something that we've lost here. However, we did build an earlier version of this framework using AnglePath that focused on that particular ability.

The Code

Want to try it out? Visit the GitHub repo for the work.

Here you'll find 4 different files:

abmManipulate - a simple template that displays the structure of the abmManipulate function

Ex. 1 Heroes - a simple model using abmManipulate that is based off of Heroes and Cowards (see section below)

Ex. 2 Cowards - a simple model using abmManipulate that is based off of Heroes and Cowards (see section below)

Ex. 3 Heroes & Cowards - an abmManipulate implementation of the Heroes and Cowards model (see section below)

The Heroes and Cowards Model

To provide a sample model using our abmManipulate framework, I used the rule set from the infamous Heroes and Cowards model. In this model, there are two types of turtles: heroes and cowards. We'll describe the model using the same format that our abmManipulate framework uses:

To setup the model:

Generate n turtles (random position and random heading)

Randomly designate each turtle as either a "hero" or a "coward"

Have each turtle pick one other turtle as its "friend"

Have each turtle pick one other turtle as its "enemy"

Then ask (conditions in italics; actions in bold):

This model works particularly well as what is called a "participatory simulation" in a classroom. Basically, have half of the students be heroes and the other half be cowards. Give the students the rules and then have them execute them in real time.

The astounding thing about this even with this simple rule set, a number of emergent patterns form depending on the initial conditions. While one of the most common outcomes are a blob of agents in the middle, there are initial conditions that lead to circular patterns, spiral patterns, a "yo-yo" pattern, a "dot", a "slinky", a wandering flock, and finally some that end up in a steady state where no turtles are moving.

The Heroes and Cowards Model abmManipulate Implementation

Here we present the setup and action-condition pairs for the Heroes and Cowards model described in the previous section.

First, we define the condition to be a hero. We do this by saying turtles who have "behavior" of "hero" and whose coordinates are within -60 and 60 are movable-heroes. Heroes act by moving towards (5% of the way) toward the midpoint between their friend and their enemy. In other words, they're moving to protect their friend from their enemy.

heros:=AllTrue[#["position"], -60<=#<=60& ]&&(#["behavior"]=="hero")&

herosAction:=Function[self,

($Turtles[[self, "position"]]=(0.95$Turtles[[self, "position"]])+(0.05(0.5($Turtles[[$Turtles[[self, "friend"]],"position"]] +$Turtles[[$Turtles[[self, "enemy"]],"position"]]))))]

Next, we define the condition to be a coward. We do this by saying turtles who have "behavior" of "coward" and whose coordinates are within -60 and 60 are movable-heroes. Cowards act by moving towards (5% of the way) toward the point opposite their friend from their enemy. In other words, they're moving to place their friend in between themselves and their enemy.

cowards:=AllTrue[#["position"], -60<=#<=60& ]&&(#["behavior"]=="coward")&

cowardsAction:=Function[self,

($Turtles[[self, "position"]]=0.95$Turtles[[self, "position"]]+(0.05$Turtles[[$Turtles[[self, "friend"]],"position"]]+(0.5($Turtles[[$Turtles[[self, "friend"]],"position"]] -$Turtles[[$Turtles[[self, "enemy"]],"position"]]))))]

Finally, we have our setup method. Here we're creating 200 turtles with 3 custom properties: "behavior", "friend", and "enemy". For each turtle, "behavior" is simply a random choice between "hero" and "coward". Each turtle then choses a random other turtle as a "friend" and another as an "enemy". Two things to notice here: 1. We use the crt function so you need to make sure to run the abmManipulate initialization code; 2. We add our turtles to a global called $Turtles (this global should be clear before you add stuff to it).

setup := $Turtles = With[{n = 200,type := RandomChoice[{"hero","coward"}]},

Join[#, <|

"behavior"->Evaluate[type],

"friend"->RandomInteger[{1,n}],

"enemy"->RandomInteger[{1,n}]|>]& /@ crt[n]

]

And that's it! That's the whole model specification. The abmManipulate framework takes care of the rest. Once you run these code cells (after having initialized the framework), your model will appear and you can interact with it as you would any other manipulate. And added feature of this framework is that you have total control over every turtle. Even in the middle of a simulation, you can easily pickup a turtle and move it around in order to effect the evolution of the model. Just remember that moving a single turtle might not do much because of the friend-enemy network between turtles.

References

Stonedahl, F., Wilensky, U., Rand, W.(2014).NetLogo Heroes and Cowards model. http://www. ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/models/HeroesandCowards.Center for Connected Learning and Computer - Based Modeling, Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL.