Introduction

I attended the Wolfram High School Summer Camp in the 2019 session. For my project, I attempted to implement a framework for creating, training, applying, and inspecting Tsetlin Machines. Tsetlin Machines are unique when compared with other methods of machine learning because they operate using Boolean operations on binary data, and the individual building blocks only require a single integer in memory. Compare this to the Neural Net, which operates by applying Calculus to floating point numbers, and where each neuron requires multiple pieces in memory corresponding to their activation function, bias, connections, weights of connections, etc. Tsetlin Machines also have the advantage that they are interpretable: once a Tsetlin Machine has been taught, it can be interpreted as a propositional formula, whereas Neural Networks, once taught, are famously "black boxes" that no one knows what's really happening inside. Furthermore, Tsetlin Machines can be used in mathematical research to produce satisfactory propositional formulas.

This community post will provide an overview about how Tsetlin Machines work. The only code in this community post will be at the very end, where I give a short example of how a Tsetlin Machine is created and trained using my framework. My full Wolfram Language implementation can be on my github account, a link to which can found at the bottom of this community post.

Tsetlin Automata

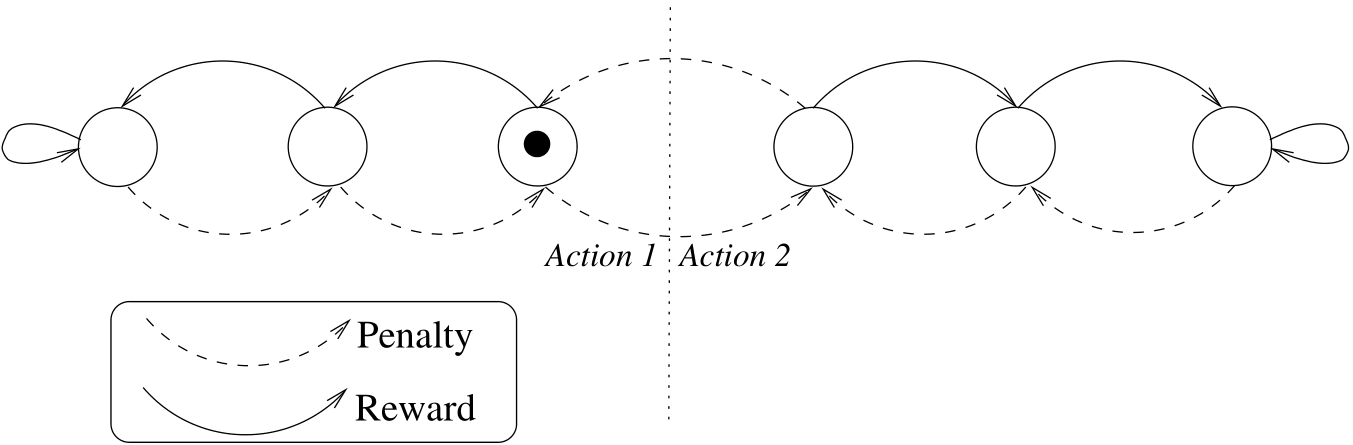

Tsetlin Machines are a kind of machine learning based on combining Tsetlin Automata to assemble a propositional formula. So, what is a Tsetlin Automaton? A Tsetlin Automaton is an extremely simple automaton that has a finite number of states ( $2n$) (image below). Based on it's state, a Tsetlin Automaton can chose between 2 actions ( $a_1$ and $a_2$). ("Action" here is an abstract concept that can basically represents a choice between two things.) It chooses the first action if it's current state is equal to a certain value ( $n$) that I call the state identifier, and chooses the second action if it's state is above the value.

So, when does a Tsetlin Automaton make this choice? Both when giving output and training. The only output ever given by a Tsetlin Automaton is its' current action. So, whenever a Tsetlin Automaton has to do pretty much anything, it starts by choosing an action and outputting it.

Image reproduced from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1804.01508.pdf

Now, how does an individual Tsetlin Automaton learn? Via punishment and reward. It's pretty simple: when a Tsetlin Automaton makes a good choice, it gets rewarded (and it's current state moves farther from the point at which it would chose the other action). When it makes a bad choice, it is punished (and it's current state moves closer to the point at which it would chose the other action).

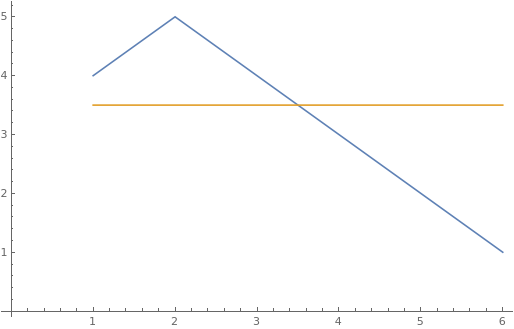

Who rewards and punishes the Tsetlin Automaton? The environment. For example, imagine that a Tsetlin Automaton (let's call him Steve) has to chose between eating two kinds of chocolate, 1 and 2. Steve has 6 states ( $n=3$). He starts randomly selects one to start with, and chooses the action of eating chocolate 2 (so his current state is 4). Eating this chocolate boosted his cognitive power, so he is rewarded (and his current state goes to 5). He takes another bite, but this time there is no effect, so he is punished (state goes back to 4). Another bite, and another failure leads to another punishment (his state goes to 3). Because Steve's state crossed the "action border" between eating chocolate 2 (state $>3)$) and eating chocolate 1 (state $\leq3$), his next choice is to eat chocolate 1. This does boost his cognitive power, so he is rewarded (state goes to 2). Another bite boosts his cognitive power again, and again he is rewarded (state goes to 1). At this point, Steve is pretty confident that chocolate 1 is the better option because it boosts his cognitive power more often, so he decides to stop training and stick with chocolate 1. Below is a graph of Steve's state (blue) as he learns (yellow is the "action tipping point").

The above story a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Tsetlin Machines

Image reproduced from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1804.01508.pdf

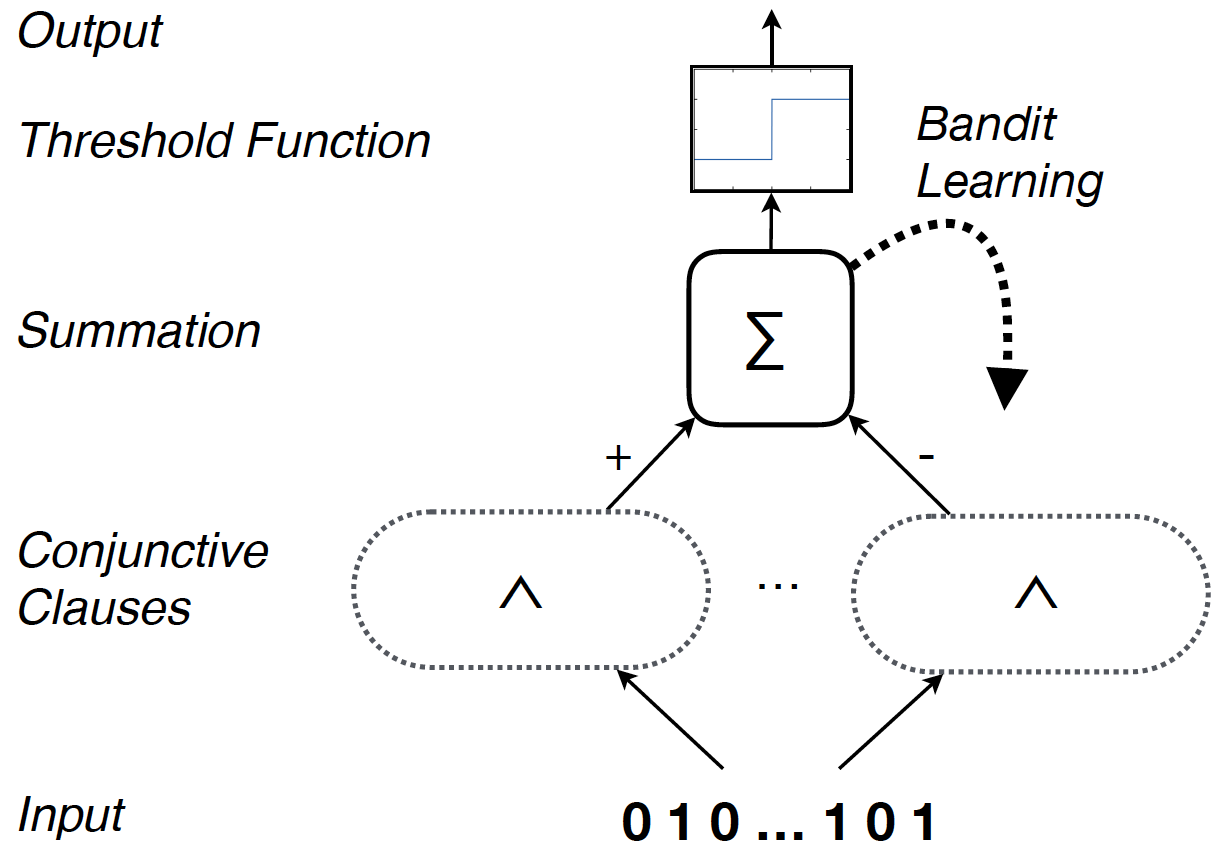

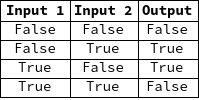

So, how do Tsetlin Automata work together to form a full Tsetlin Machine? By learning which inputs to a Tsetlin Machine are important. But before learning can be explained, the process of how a Tsetlin Machine calculates its' outputs must be explained. For this purpose, consider a Tsetlin Machine that has not yet been trained, trying to learn the simple 2-input XOR operation:

Input to a Tsetlin Machine is a list of Booleans (in this case, the list is length 2 because the goal is to emulate XOR, which takes 2 inputs). After the input is taken, it is duplicated and inverted. So, the complete input ends up taking the form {{a, b}, {NOT a, NOT b}}. For example, an input of {True, False} would produce {{True, False}, {False, True}}.

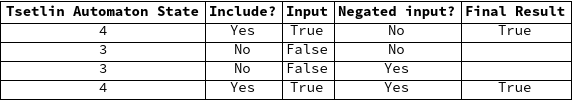

Once the complete input is calculated, it is fed to a team of Tsetlin Automata (which are randomly initialized). There are a number of Tsetlin Automata equal to length of the input-- that is, each Automata corresponds to one input value. Based on its current state, each Automata chooses either to include or exclude the input (if the current state is less than or equal to the state identifier, the input is excluded. Otherwise, it is included).

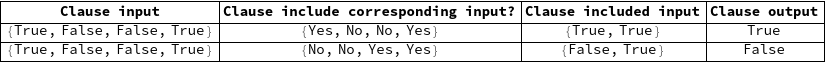

Any included inputs in the team are then ANDed together. There actually can be multiple teams of Tsetlin Automata, each of which chooses which inputs to include and exclude independently of the other teams (as well as ANDs the results independently).

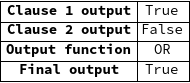

Once each team of Tsetlin Automata has calculated their final, joint result, the outputs from that result is sent to an output function. There are many different output functions, the two most common of which are OR and the Alternating Sum. For this example, I will use OR.

The final output from this Tsetlin Machine given the input of {True, False} is True, which happens to be correct. However, this machine will fail on an input of {False, True}, and will output, instead of the expected True, a False. So how does the Tsetlin Machine learn that this is wrong? Through feedback.

There are 2 different kinds of feedback that a Tsetlin Machine can provide back to its' Automata: Type 1 and Type 2. Although the exact details of the types of feedback are rather complicated, the point of each is simple: Type 1 feedback combats false negative output (when the machine outputted a False when it should have outputted a True), and Type 2 feedback combats false positive output (when the machine outputted a True when it should have outputted a False). Feedback is given to a clause at a time, based on a function provided by the user (at least in my implementation) called a "feedback decider" which takes a series of arguments that contain information about the current state of the machine . Each kind of output function requires a different kind of feedback decider, to make sure the feedback is correctly assigned. At the automata level, feedback takes the form of a weighted reward or punishment (a reward or punishment that probabilistically happens), based on an s-value (which controls precision) specified by the person training the machine. There is more information in the original paper and in my implementation about how feedback works.

In short, feedback punishes or rewards automata to make them more likely to include or exclude inputs correctly.

After feedback is given, then a new input is given to the machine and the process repeats.

One detail that is important to note is that Tsetlin Machines can have multiple outputs, each of which is trained independently and has their own Tsetlin Automata teams.

Using the Framework

The following chunk of code shows how one would train a Tsetlin Machine from scratch to learn the XOR operation using my framework:

TsetlinMachineTrain[ (* function that trains a Tsetlin Machine *)

TsetlinMachineInitialize[ (* make a new Tsetlin Machine *)

3, (* state identifier 3 *)

2, (* 2 inputs *)

2, (* 2 clauses *)

{TsetlinUtilityOr}], (* one output that uses the function TsetlinUtilityOr *)

{{False, False}, {False, True}, {True, False}, {True, True}}, (* training input data *)

{{False}, {True}, {True}, {False}}, (* training output data *)

{{False, False}, {False, True}, {True, False}, {True, True}}, (* testing input data *)

{{False}, {True}, {True}, {False}}, (* testing output data *)

9, (* s-value (precision) *)

TsetlinUtilityOrFeedbackDecider[#1, #2, #3, #4, #5, #6, 2] &, (* feedback decider with threshold set to 2, more info in paper *)

1.00] (* train until it has 100% accuracy *)

Further Resources