Introduction

In this document we describe the design and implementation of a (software programming) monad, [Wk1], for Latent Semantic Analysis workflows specification and execution. The design and implementation are done with Mathematica / Wolfram Language (WL).

What is Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA)? : A statistical method (or a technique) for finding relationships in natural language texts that is based on the so called Distributional hypothesis, [Wk2, Wk3]. (The Distributional hypothesis can be simply stated as "linguistic items with similar distributions have similar meanings"; for an insightful philosophical and scientific discussion see [MS1].) LSA can be seen as the application of Dimensionality reduction techniques over matrices derived with the Vector space model.

The goal of the monad design is to make the specification of LSA workflows (relatively) easy and straightforward by following a certain main scenario and specifying variations over that scenario.

The monad is named LSAMon and it is based on the State monad package "StateMonadCodeGenerator.m", [AAp1, AA1], the document-term matrix making package "DocumentTermMatrixConstruction.m", [AAp4, AA2], the Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NNMF) package "NonNegativeMatrixFactorization.m", [AAp5, AA2], and the package "SSparseMatrix.m", [AAp2, AA5], that provides matrix objects with named rows and columns.

The data for this document is obtained from WL's repository and it is manipulated into a certain ready-to-utilize form (and uploaded to GitHub.)

The monadic programming design is used as a Software Design Pattern. The LSAMon monad can be also seen as a Domain Specific Language (DSL) for the specification and programming of machine learning classification workflows.

Here is an example of using the LSAMon monad over a collection of documents that consists of 233 US state of union speeches.

The table above is produced with the package "MonadicTracing.m", [AAp2, AA1], and some of the explanations below also utilize that package.

As it was mentioned above the monad LSAMon can be seen as a DSL. Because of this the monad pipelines made with LSAMon are sometimes called "specifications".

Remark: In this document with "term" we mean "a word, a word stem, or other type of token."

Remark: LSA and Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI) are considered more or less to be synonyms. I think that "latent semantic analysis" sounds more universal and that "latent semantic indexing" as a name refers to a specific Information Retrieval technique. Below we refer to "LSI functions" like "IDF" and "TF-IDF" that are applied within the generic LSA workflow.

Contents description

The document has the following structure.

The sections "Package load" and "Data load" obtain the needed code and data.

The sections "Design consideration" and "Monad design" provide motivation and design decisions rationale.

The sections "LSAMon overview", "Monad elements", and "The utilization of SSparseMatrix objects" provide technical descriptions needed to utilize the LSAMon monad .

- (Using a fair amount of examples.)

The section "Unit tests" describes the tests used in the development of the LSAMon monad.

- (The random pipelines unit tests are especially interesting.)

The section "Future plans" outlines future directions of development.

The section "Implementation notes" just says that LSAMon's development process and this document follow the ones of the classifications workflows monad ClCon, [AA6].

Remark: One can read only the sections "Introduction", "Design consideration", "Monad design", and "LSAMon overview". That set of sections provide a fairly good, programming language agnostic exposition of the substance and novel ideas of this document.

Package load

The following commands load the packages [AAp1--AAp7]:

Import["https://raw.githubusercontent.com/antononcube/MathematicaForPrediction/master/MonadicProgramming/MonadicLatentSemanticAnalysis.m"]

Import["https://raw.githubusercontent.com/antononcube/MathematicaForPrediction/master/MonadicProgramming/MonadicTracing.m"]

Data load

In this section we load data that is used in the rest of the document. The text data was obtained through WL's repository, transformed in a certain more convenient form, and uploaded to GitHub.

The text summarization and plots are done through LSAMon, which in turn uses the function RecordsSummary from the package "MathematicaForPredictionUtilities.m", [AAp7].

Hamlet

textHamlet =

ToString /@

Flatten[Import["https://raw.githubusercontent.com/antononcube/MathematicaVsR/master/Data/MathematicaVsR-Data-Hamlet.csv"]];

TakeLargestBy[

Tally[DeleteStopwords[ToLowerCase[Flatten[TextWords /@ textHamlet]]]], #[[2]] &, 20]

(* {{"ham", 358}, {"lord", 225}, {"king", 196}, {"o", 124}, {"queen", 120},

{"shall", 114}, {"good", 109}, {"hor", 109}, {"come", 107}, {"hamlet", 107},

{"thou", 105}, {"let", 96}, {"thy", 86}, {"pol", 86}, {"like", 81}, {"sir", 75},

{"'t", 75}, {"know", 74}, {"enter", 73}, {"th", 72}} *)

LSAMonUnit[textHamlet]?LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix?LSAMonEchoDocumentTermMatrixStatistics;

USA state of union speeches

url = "https://github.com/antononcube/MathematicaVsR/blob/master/Data/MathematicaVsR-Data-StateOfUnionSpeeches.JSON.zip?raw=true";

str = Import[url, "String"];

filename = First@Import[StringToStream[str], "ZIP"];

aStateOfUnionSpeeches = Association@ImportString[Import[StringToStream[str], {"ZIP", filename, "String"}], "JSON"];

lsaObj =

LSAMonUnit[aStateOfUnionSpeeches]?

LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix?

LSAMonEchoDocumentTermMatrixStatistics["LogBase" -> 10];

TakeLargest[ColumnSumsAssociation[lsaObj?LSAMonTakeDocumentTermMatrix], 12]

(* <|"government" -> 7106, "states" -> 6502, "congress" -> 5023,

"united" -> 4847, "people" -> 4103, "year" -> 4022,

"country" -> 3469, "great" -> 3276, "public" -> 3094, "new" -> 3022,

"000" -> 2960, "time" -> 2922|> *)

Stop words

In some of the examples below we want to explicitly specify the stop words. Here are stop words derived using the built-in functions DictionaryLookup and DeleteStopwords.

stopWords = Complement[DictionaryLookup["*"], DeleteStopwords[DictionaryLookup["*"]]];

Short[stopWords]

(* {"a", "about", "above", "across", "add-on", "after", "again", <<290>>,

"you'll", "your", "you're", "yours", "yourself", "yourselves", "you've" } *)

Design considerations

The steps of the main LSA workflow addressed in this document follow.

Get a collection of documents with associated ID's.

Create a document-term matrix.

Here we apply the Bag-or-words model and Vector space model.

The sequential order of the words is ignored and each document is represented as a point in a multi-dimensional vector space.

That vector space axes correspond to the unique words found in the whole document collection.

Consider the application of stemming rules.

Consider the removal of stop words.

Apply matrix-entries weighting functions.

Those functions come from LSI.

Functions like "IDF", "TF-IDF", "GFIDF".

Extract topics.

One possible statistical way of doing this is with Dimensionality reduction.

We consider using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NNMF).

Make and display the topics table.

Extract and display a statistical thesaurus of selected words.

Map search queries or unseen documents over the extracted topics.

Find the most important documents in the document collection. (Optional.)

The following flow-chart corresponds to the list of steps above.

In order to address:

the introduction of new elements in LSA workflows,

workflows elements variability, and

workflows iterative changes and refining,

it is beneficial to have a DSL for LSA workflows. We choose to make such a DSL through a [functional programming monad](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monad_(functional_programming)), [[Wk1](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monad_(functional_programming)), AA1].

Here is a quote from [[Wk1](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monad_(functional_programming))] that fairly well describes why we choose to make a classification workflow monad and hints on the desired properties of such a monad.

[...] The monad represents computations with a sequential structure: a monad defines what it means to chain operations together. This enables the programmer to build pipelines that process data in a series of steps (i.e. a series of actions applied to the data), in which each action is decorated with the additional processing rules provided by the monad. [...]

Monads allow a programming style where programs are written by putting together highly composable parts, combining in flexible ways the possible actions that can work on a particular type of data. [...]

Remark: Note that quote from [Wk1] refers to chained monadic operations as "pipelines". We use the terms "monad pipeline" and "pipeline" below.

Monad design

The monad we consider is designed to speed-up the programming of LSA workflows outlined in the previous section. The monad is named LSAMon for "Latent Semantic Analysis** Mon**ad".

We want to be able to construct monad pipelines of the general form:

LSAMon is based on the [State monad](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monad_(functional_programming)#State_monads), [Wk1, AA1], so the monad pipeline form (1) has the following more specific form:

This means that some monad operations will not just change the pipeline value but they will also change the pipeline context.

In the monad pipelines of LSAMon we store different objects in the contexts for at least one of the following two reasons.

The object will be needed later on in the pipeline, or

The object is (relatively) hard to compute.

Such objects are document-term matrix, Dimensionality reduction factors and the related topics.

Let us list the desired properties of the monad.

Rapid specification of non-trivial LSA workflows.

The text data supplied to the monad can be: (i) a list of strings, or (ii) an association with string values.

The monad uses the Linear vector space model .

The document-term frequency matrix can be created after removing stop words and/or word stemming.

It is easy to specify and apply different LSI weight functions. (Like "IDF" or "GFIDF".)

The monad can do Dimensional reduction with SVD and NNMF and the corresponding matrix factors are retrievable with monad functions.

Documents (or query strings) external to the monad are easily mapped into monad's Linear vector space of terms and Linear vector space of topics.

The monad allows of cursory examination and summarization of the data.

The pipeline values can be of different types. (Most monad functions modify the pipeline value; some modify the context; some just echo results.)

It is easy to obtain the pipeline value, context, and different context objects for manipulation outside of the monad.

It is easy to tabulate extracted topics and related statistical thesauri.

The LSAMon components and their interactions are fairly simple.

The main LSAMon operations implicitly put in the context or utilize from the context the following objects:

document-term matrix,

the factors obtained by matrix factorization algorithms,

LSI weight functions specifications,

extracted topics.

Note the that the monadic set of types of LSAMon pipeline values is fairly heterogenous and certain awareness of "the current pipeline value" is assumed when composing LSAMon pipelines.

Obviously, we can put in the context any object through the generic operations of the State monad of the package "StateMonadGenerator.m", [AAp1].

LSAMon overview

When using a monad we lift certain data into the "monad space", using monad's operations we navigate computations in that space, and at some point we take results from it.

With the approach taken in this document the "lifting" into the LSAMon monad is done with the function LSAMonUnit. Results from the monad can be obtained with the functions LSAMonTakeValue, LSAMonContext, or with the other LSAMon functions with the prefix "LSAMonTake" (see below.)

Here is a corresponding diagram of a generic computation with the LSAMon monad:

Remark: It is a good idea to compare the diagram with formulas (1) and (2).

Let us examine a concrete LSAMon pipeline that corresponds to the diagram above. In the following table each pipeline operation is combined together with a short explanation and the context keys after its execution.

Here is the output of the pipeline:

The LSAMon functions are separated into four groups:

Monad functions interaction with the pipeline value and context

An overview of the those functions is given in the tables in next two sub-sections. The next section, "Monad elements", gives details and examples for the usage of the LSAMon operations.

State monad functions

Here are the LSAMon State Monad functions (generated using the prefix "LSAMon", [AAp1, AA1].)

Main monad functions

Here are the usage descriptions of the main (not monad-supportive) LSAMon functions, which are explained in detail in the next section.

Monad elements

In this section we show that LSAMon has all of the properties listed in the previous section.

The monad head

The monad head is LSAMon. Anything wrapped in LSAMon can serve as monad's pipeline value. It is better though to use the constructor LSAMonUnit. (Which adheres to the definition in [Wk1].)

LSAMon[textHamlet, <||>]?LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix[Automatic, Automatic]?LSAMonEchoFunctionContext[Short];

Lifting data to the monad

The function lifting the data into the monad QRMon is QRMonUnit.

The lifting to the monad marks the beginning of the monadic pipeline. It can be done with data or without data. Examples follow.

LSAMonUnit[textHamlet]?LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix?LSAMonTakeDocumentTermMatrix

LSAMonUnit[]?LSAMonSetDocuments[textHamlet]?LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix?LSAMonTakeDocumentTermMatrix

(See the sub-section "Setters, droppers, and takers" for more details of setting and taking values in LSAMon contexts.)

Currently the monad can deal with data in the following forms:

Generally, WL makes it easy to extract columns datasets order to obtain vectors or matrices, so datasets are not currently supported in LSAMon.

Making of the document-term matrix

As it was mentioned above with "term" we mean "a word or a stemmed word". Here is are examples of stemmed words.

WordData[#, "PorterStem"] & /@ {"consequential", "constitution", "forcing", ""}

The fundamental model of LSAMon is the so called Vector space model (or the closely related Bag-of-words model.) The document-term matrix is a linear vector space representation of the documents collection. That representation is further used in LSAMon to find topics and statistical thesauri.

Here is an example of ad hoc construction of a document-term matrix using a couple of paragraphs from "Hamlet".

inds = {10, 19};

aTempText = AssociationThread[inds, textHamlet[[inds]]]

MatrixForm @ CrossTabulate[Flatten[KeyValueMap[Thread[{#1, #2}] &, TextWords /@ ToLowerCase[aTempText]], 1]]

When we construct the document-term matrix we (often) want to stem the words and (almost always) want to remove stop words. LSAMon's function LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix makes the document-term matrix and takes specifications for stemming and stop words.

lsaObj =

LSAMonUnit[textHamlet]?

LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix["StemmingRules" -> Automatic, "StopWords" -> Automatic]?

LSAMonEchoFunctionContext[ MatrixPlot[#documentTermMatrix] &]?

LSAMonEchoFunctionContext[TakeLargest[ColumnSumsAssociation[#documentTermMatrix], 12] &];

We can retrieve the stop words used in a monad with the function LSAMonTakeStopWords.

Short[lsaObj?LSAMonTakeStopWords]

We can retrieve the stemming rules used in a monad with the function LSAMonTakeStemmingRules.

Short[lsaObj?LSAMonTakeStemmingRules]

The specification Automatic for stemming rules uses WordData[#,"PorterStem"]&.

Instead of the options style signature we can use positional signature.

Options style: LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix["StemmingRules" -> {}, "StopWords" -> Automatic] .

Positional style: LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix[{}, Automatic] .

LSI weight functions

After making the document-term matrix we will most likely apply LSI weight functions, [Wk2], like "GFIDF" and "TF-IDF". (This follows the "standard" approach used in search engines for calculating weights for document-term matrices; see [MB1].)

Frequency matrix

We use the following definition of the frequency document-term matrix $F$.

Each entry $f_{i j}$ of the matrix $F$ is the number of occurrences of the term $j$ in the document $i$.

Weights

Each entry of the weighted document-term matrix $M$ derived from the frequency document-term matrix $F$ is expressed with the formula

where $g_j$ -- global term weight; $l_{i j}$ -- local term weight; $d_i$ -- normalization weight.

Various formulas exist for these weights and one of the challenges is to find the right combination of them when using different document collections.

Here is a table of weight functions formulas.

Computation specifications

LSAMon function LSAMonApplyTermWeightFunctions delegates the LSI weight functions application to the package "DocumentTermMatrixConstruction.m", [AAp4].

Here is an example.

lsaHamlet = LSAMonUnit[textHamlet]?LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix;

wmat =

lsaHamlet?

LSAMonApplyTermWeightFunctions["IDF", "TermFrequency", "Cosine"]?

LSAMonTakeWeightedDocumentTermMatrix;

TakeLargest[ColumnSumsAssociation[wmat], 6]

Instead of using the positional signature of LSAMonApplyTermWeightFunctions we can specify the LSI functions using options.

wmat2 =

lsaHamlet?

LSAMonApplyTermWeightFunctions["GlobalWeightFunction" -> "IDF", "LocalWeightFunction" -> "TermFrequency", "NormalizerFunction" -> "Cosine"]?

LSAMonTakeWeightedDocumentTermMatrix;

TakeLargest[ColumnSumsAssociation[wmat2], 6]

Here we are summaries of the non-zero values of the weighted document-term matrix derived with different combinations of global, local, and normalization weight functions.

Magnify[#, 0.8] &@Multicolumn[Framed /@ #, 6] &@Flatten@

Table[

(wmat =

lsaHamlet?

LSAMonApplyTermWeightFunctions[gw, lw, nf]?

LSAMonTakeWeightedDocumentTermMatrix;

RecordsSummary[SparseArray[wmat]["NonzeroValues"],

List@StringRiffle[{gw, lw, nf}, ", "]]),

{gw, {"IDF", "GFIDF", "Binary", "None", "ColumnStochastic"}},

{lw, {"Binary", "Log", "None"}},

{nf, {"Cosine", "None", "RowStochastic"}}]

AutoCollapse[]

Extracting topics

Streamlining topic extraction is one of the main reasons LSAMon was implemented. The topic extraction correspond to the so called "syntagmatic" relationships between the terms, [MS1].

Theoretical outline

The original weighed document-term matrix $M$ is decomposed into the matrix factors $W$ and $H$.

$M \approx W . H, W \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times k}, H \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times n}.$

The $i$-th row of $M$ is expressed with the $i$-th row of $W$ multiplied by $H$.

The rows of $H$ are the topics. SVD produces orthogonal topics; NNMF does not.

The $i$-the document of the collection corresponds to the $i$-th row $W$. Finding the Nearest Neighbors (NN's) of the $i$-th document using the rows similarity of the matrix $W$ gives document NN's through topic similarity.

The terms correspond to the columns of $H$. Finding NN's based on similarities of $H$'s columns produces statistical thesaurus entries.

The term groups provided by $H$'s rows correspond to "syntagmatic" relationships. Using similarities of $H$'s columns we can produce term clusters that correspond to "paradigmatic" relationships.

Computation specifications

Here is an example using the play "Hamlet" in which we specify additional stop words.

stopWords2 = {"enter", "exit", "[exit", "ham", "hor", "laer", "pol", "oph", "thy", "thee", "act", "scene"};

SeedRandom[2381]

lsaHamlet =

LSAMonUnit[textHamlet]?

LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix["StemmingRules" -> Automatic, "StopWords" -> Join[stopWords, stopWords2]]?

LSAMonApplyTermWeightFunctions["GlobalWeightFunction" -> "IDF", "LocalWeightFunction" -> "None", "NormalizerFunction" -> "Cosine"]?

LSAMonExtractTopics["NumberOfTopics" -> 12, "MinNumberOfDocumentsPerTerm" -> 10, Method -> "NNMF", "MaxSteps" -> 20]?

LSAMonEchoTopicsTable["NumberOfTableColumns" -> 6, "NumberOfTerms" -> 10];

Here is an example using the USA presidents "state of union" speeches.

SeedRandom[7681]

lsaSpeeches =

LSAMonUnit[aStateOfUnionSpeeches]?

LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix["StemmingRules" -> Automatic, "StopWords" -> Automatic]?

LSAMonApplyTermWeightFunctions["GlobalWeightFunction" -> "IDF", "LocalWeightFunction" -> "None", "NormalizerFunction" -> "Cosine"]?

LSAMonExtractTopics["NumberOfTopics" -> 36, "MinNumberOfDocumentsPerTerm" -> 40, Method -> "NNMF", "MaxSteps" -> 12]?

LSAMonEchoTopicsTable["NumberOfTableColumns" -> 6, "NumberOfTerms" -> 10];

Note that in both examples:

stemming is used when creating the document-term matrix,

the default LSI re-weighting functions are used: "IDF", "None", "Cosine",

the dimension reduction algorithm NNMF is used.

Things to keep in mind.

The interpretability provided by NNMF comes at a price.

NNMF is prone to get stuck into local minima, so several topic extractions (and corresponding evaluations) have to be done.

We would get different results with different NNMF runs using the same parameters. (NNMF uses random numbers initialization.)

The NNMF topic vectors are not orthogonal.

SVD is much faster than NNMF, but it topic vectors are hard to interpret.

Generally, the topics derived with SVD are stable, they do not change with different runs with the same parameters.

The SVD topics vectors are orthogonal, which provides for quick to find representations of documents not in the monad's document collection.

The document-topic matrix $W$ has column names that are automatically derived from the top three terms in each topic.

ColumnNames[lsaHamlet?LSAMonTakeW]

(* {"player-plai-welcom", "ro-lord-sir", "laert-king-attend",

"end-inde-make", "state-room-castl", "daughter-pass-love",

"hamlet-ghost-father", "father-thou-king",

"rosencrantz-guildenstern-king", "ophelia-queen-poloniu",

"answer-sir-mother", "horatio-attend-gentleman"} *)

Of course the row names of $H$ have the same names.

RowNames[lsaHamlet?LSAMonTakeH]

(* {"player-plai-welcom", "ro-lord-sir", "laert-king-attend",

"end-inde-make", "state-room-castl", "daughter-pass-love",

"hamlet-ghost-father", "father-thou-king",

"rosencrantz-guildenstern-king", "ophelia-queen-poloniu",

"answer-sir-mother", "horatio-attend-gentleman"} *)

Extracting statistical thesauri

The statistical thesaurus extraction corresponds to the "paradigmatic" relationships between the terms, [MS1].

Here is an example over the State of Union speeches.

entryWords = {"bank", "war", "economy", "school", "port", "health", "enemy", "nuclear"};

lsaSpeeches?

LSAMonExtractStatisticalThesaurus["Words" -> Map[WordData[#, "PorterStem"] &, entryWords], "NumberOfNearestNeighbors" -> 12]?

LSAMonEchoStatisticalThesaurus;

In the code above: (i) the options signature style is used, (ii) the statistical thesaurus entry words are stemmed first.

We can also call LSAMonEchoStatisticalThesaurus directly without calling LSAMonExtractStatisticalThesaurus first.

lsaSpeeches?

LSAMonEchoStatisticalThesaurus["Words" -> Map[WordData[#, "PorterStem"] &, entryWords], "NumberOfNearestNeighbors" -> 12];

Mapping queries and documents to terms

One of the most natural operations is to find the representation of an arbitrary document (or sentence or a list of words) in monad's Linear vector space of terms. This is done with the function LSAMonRepresentByTerms.

Here is an example in which a sentence is represented as a one-row matrix (in that space.)

obj =

lsaHamlet?

LSAMonRepresentByTerms["Hamlet, Prince of Denmark killed the king."]?

LSAMonEchoValue;

Here we display only the non-zero columns of that matrix.

obj?

LSAMonEchoFunctionValue[MatrixForm[Part[#, All, Keys[Select[SSparseMatrix`ColumnSumsAssociation[#], # > 0& ]]]]& ];

Transformation steps

Assume that LSAMonRepresentByTerms is given a list of sentences. Then that function performs the following steps.

1. The sentence is split into a list of words.

2. If monad's document-term matrix was made by removing stop words the same stop words are removed from the list of words.

3. If monad's document-term matrix was made by stemming the same stemming rules are applied to the list of words.

4. The LSI global weights and the LSI local weight and normalizer functions are applied to sentence's contingency matrix.

Equivalent representation

Let us look convince ourselves that documents used in the monad to built the weighted document-term matrix have the same representation as the corresponding rows of that matrix.

Here is an association of documents from monad's document collection.

inds = {6, 10};

queries = Part[lsaHamlet?LSAMonTakeDocuments, inds];

queries

(* <|"id.0006" -> "Getrude, Queen of Denmark, mother to Hamlet. Ophelia, daughter to Polonius.",

"id.0010" -> "ACT I. Scene I. Elsinore. A platform before the Castle."|> *)

lsaHamlet?

LSAMonRepresentByTerms[queries]?

LSAMonEchoFunctionValue[MatrixForm[Part[#, All, Keys[Select[SSparseMatrix`ColumnSumsAssociation[#], # > 0& ]]]]& ];

lsaHamlet?

LSAMonEchoFunctionContext[MatrixForm[Part[Slot["weightedDocumentTermMatrix"], inds, Keys[Select[SSparseMatrix`ColumnSumsAssociation[Part[Slot["weightedDocumentTermMatrix"], inds, All]], # > 0& ]]]]& ];

Mapping queries and documents to topics

Another natural operation is to find the representation of an arbitrary document (or a list of words) in monad's Linear vector space of topics. This is done with the function LSAMonRepresentByTopics.

Here is an example.

inds = {6, 10};

queries = Part[lsaHamlet?LSAMonTakeDocuments, inds];

Short /@ queries

(* <|"id.0006" -> "Getrude, Queen of Denmark, mother to Hamlet. Ophelia, daughter to Polonius.",

"id.0010" -> "ACT I. Scene I. Elsinore. A platform before the Castle."|> *)

lsaHamlet?

LSAMonRepresentByTopics[queries]?

LSAMonEchoFunctionValue[MatrixForm[Part[#, All, Keys[Select[SSparseMatrix`ColumnSumsAssociation[#], # > 0& ]]]]& ];

lsaHamlet?

LSAMonEchoFunctionContext[MatrixForm[Part[Slot["W"], inds, Keys[Select[SSparseMatrix`ColumnSumsAssociation[Part[Slot["W"], inds, All]], # > 0& ]]]]& ];

Theory

In order to clarify what the function LSAMonRepresentByTopics is doing let us go through the formulas it is based on.

The original weighed document-term matrix $M$ is decomposed into the matrix factors $W$ and $H$.

$M \approx W . H, W \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times k}, H \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times n}$

The $i$-th row of $M$ is expressed with the $i$-th row of $W$ multiplied by $H$.

$m_{i} \approx w_{i} . H .$

For a query vector $q_0 \in \mathbb{R}^m$ we want to find its topics representation vector $x \in \mathbb{R}^k$:

$q_{0} \approx x . H .$

Denote with $H^{(-1)}$ the inverse or pseudo-inverse matrix of $H$. We have:

$q_{0} . H^{(-1)} \approx (x . H ) . H^{(-1)} = x . ( H . H^{(-1)} ) = x . I,$

$x \in \mathbb{R}^{k}, H^{(-1)} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times k}, I \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times k}.$

In LSAMon for SVD $H^{(-1)} = H^T$; for NNMF $H^{(-1)}$ is the pseudo-inverse of $H$.

The vector $x$ obtained with LSAMonRepresentByTopics.

Tags representation

Sometimes we want to find the topics representation of tags associated with monad's documents and the tag-document associations are one-to-many. See [AA3].

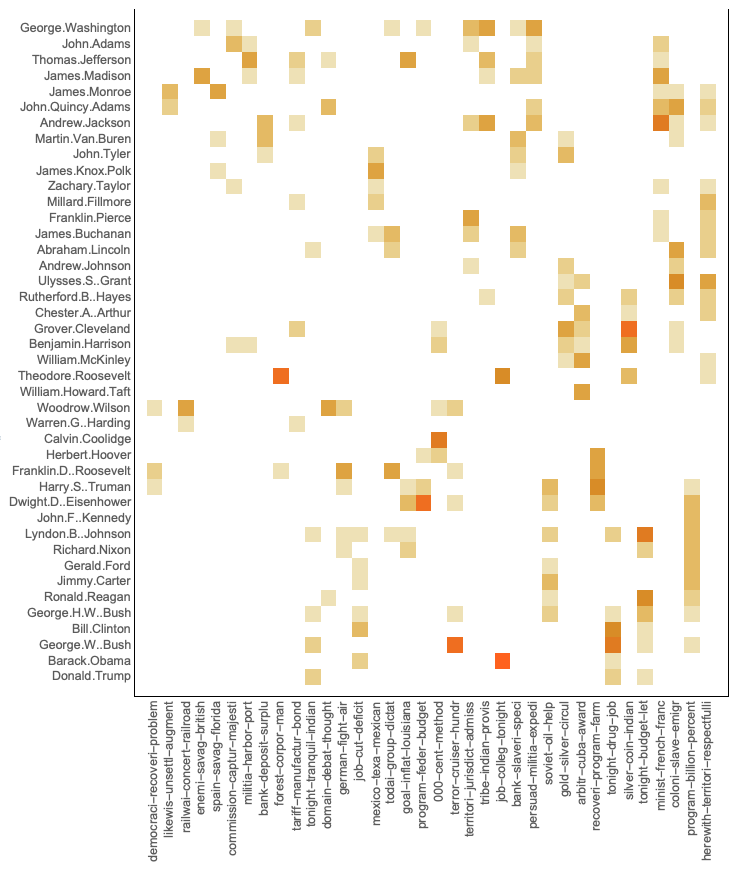

Let us consider a concrete example -- we want to find what topics correspond to the different presidents in the collection of State of Union speeches.

Here we find the document tags (president names in this case.)

tags = StringReplace[

RowNames[

lsaSpeeches?LSAMonTakeDocumentTermMatrix],

RegularExpression[".\\d\\d\\d\\d-\\d\\d-\\d\\d"] -> ""];

Short[tags]

Here is the number of unique tags (president names.)

Length[Union[tags]]

(* 42 *)

Here we compute the tag-topics representation matrix using the function LSAMonRepresentDocumentTagsByTopics.

tagTopicsMat =

lsaSpeeches?

LSAMonRepresentDocumentTagsByTopics[tags]?

LSAMonTakeValue

Here is a heatmap plot of the tag-topics matrix made with the package "HeatmapPlot.m", [AAp11].

HeatmapPlot[tagTopicsMat[[All, Ordering@ColumnSums[tagTopicsMat]]], DistanceFunction -> None, ImageSize -> Large]

Finding the most important documents

There are several algorithms we can apply for finding the most important documents in the collection. LSAMon utilizes two types algorithms: (1) graph centrality measures based, and (2) matrix factorization based. With certain graph centrality measures the two algorithms are equivalent. In this sub-section we demonstrate the matrix factorization algorithm (that uses SVD.)

Definition: The most important sentences have the most important words and the most important words are in the most important sentences.

That definition can be used to derive an iterations-based model that can be expressed with SVD or eigenvector finding algorithms, [LE1].

Here we pick an important part of the play "Hamlet".

focusText =

First@Pick[textHamlet, StringMatchQ[textHamlet, ___ ~~ "to be" ~~ __ ~~ "or not to be" ~~ ___, IgnoreCase -> True]];

Short[focusText]

(* "Ham. To be, or not to be- that is the question: Whether 'tis ....y.

O, woe is me T' have seen what I have seen, see what I see!" *)

LSAMonUnit[StringSplit[ToLowerCase[focusText], {",", ".", ";", "!", "?"}]]?

LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix["StemmingRules" -> {}, "StopWords" -> Automatic]?

LSAMonApplyTermWeightFunctions?

LSAMonFindMostImportantDocuments[3]?

LSAMonEchoFunctionValue[GridTableForm];

Setters, droppers, and takers

The values from the monad context can be set, obtained, or dropped with the corresponding "setter", "dropper", and "taker" functions as summarized in a previous section.

For example:

p = LSAMonUnit[textHamlet]?LSAMonMakeDocumentTermMatrix[Automatic, Automatic];

p?LSAMonTakeMatrix

If other values are put in the context they can be obtained through the (generic) function LSAMonTakeContext, [AAp1]:

Short@(p?QRMonTakeContext)["documents"]

(* <|"id.0001" -> "1604", "id.0002" -> "THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET, PRINCE OF DENMARK", <<220>>, "id.0223" -> "THE END"|> *)

Another generic function from [AAp1] is LSAMonTakeValue (used many times above.)

Here is an example of the "data dropper" LSAMonDropDocuments:

Keys[p?LSAMonDropDocuments?QRMonTakeContext]

(* {"documentTermMatrix", "terms", "stopWords", "stemmingRules"} *)

(The "droppers" simply use the state monad function LSAMonDropFromContext, [AAp1]. For example, LSAMonDropDocuments is equivalent to LSAMonDropFromContext["documents"].)

The utilization of SSparseMatrix objects

The LSAMon monad heavily relies on SSparseMatrix objects, [AAp6, AA5], for internal representation of data and computation results.

A SSparseMatrix object is a matrix with named rows and columns.

Here is an example.

n = 6;

rmat = ToSSparseMatrix[

SparseArray[{{1, 2} -> 1, {4, 5} -> 1}, {n, n}],

"RowNames" -> RandomSample[CharacterRange["A", "Z"], n],

"ColumnNames" -> RandomSample[CharacterRange["a", "z"], n]];

MatrixForm[rmat]

In this section we look into some useful SSparseMatrix idioms applied within LSAMon.

Visualize with sorted rows and columns

In some situations it is beneficial to sort rows and columns of the (weighted) document-term matrix.

docTermMat =

lsaSpeeches?LSAMonTakeDocumentTermMatrix;

MatrixPlot[docTermMat[[Ordering[RowSums[docTermMat]], Ordering[ColumnSums[docTermMat]]]], MaxPlotPoints -> 300, ImageSize -> Large]

Finding the most and least popular terms

The most popular terms in the document collection can be found through the association of the column sums of the document-term matrix.

TakeLargest[ColumnSumsAssociation[lsaSpeeches?LSAMonTakeDocumentTermMatrix], 10]

(* <|"state" -> 8852, "govern" -> 8147, "year" -> 6362, "nation" -> 6182,

"congress" -> 5040, "unit" -> 5040, "countri" -> 4504,

"peopl" -> 4306, "american" -> 3648, "law" -> 3496|> *)

Similarly for the lest popular terms.

TakeSmallest[

ColumnSumsAssociation[

lsaSpeeches?LSAMonTakeDocumentTermMatrix], 10]

(* <|"036" -> 1, "027" -> 1, "_____________________" -> 1, "0111" -> 1,

"006" -> 1, "0000" -> 1, "0001" -> 1, "______________________" -> 1,

"____" -> 1, "____________________" -> 1|> *)

Showing only non-zero columns

In some cases we want to show only columns of the data or computation results matrices that have non-zero elements.

Here is an example (similar to other examples in the previous section.)

lsaHamlet?

LSAMonRepresentByTerms[{"this country is rotten",

"where is my sword my lord",

"poison in the ear should be in the play"}]?

LSAMonEchoFunctionValue[ MatrixForm[#1[[All, Keys[Select[ColumnSumsAssociation[#1], #1 > 0 &]]]]] &];

In the pipeline code above: (i) from the list of queries a representation matrix is made, (ii) that matrix is assigned to the pipeline value, (iii) in the pipeline echo value function the non-zero columns are selected with by using the keys of the non-zero elements of the association obtained with ColumnSumsAssociation.

Similarities based on representation by terms

Here is way to compute the similarity matrix of different sets of documents that are not required to be in monad's document collection.

sMat1 =

lsaSpeeches?

LSAMonRepresentByTerms[ aStateOfUnionSpeeches[[ Range[-5, -2] ]] ]?

LSAMonTakeValue

sMat2 =

lsaSpeeches?

LSAMonRepresentByTerms[ aStateOfUnionSpeeches[[ Range[-7, -3] ]] ]?

LSAMonTakeValue

MatrixForm[sMat1.Transpose[sMat2]]

Similarities based on representation by topics

Similarly to weighted Boolean similarities matrix computation above we can compute a similarity matrix using the topics representations. Note that an additional normalization steps is required.

sMat1 =

lsaSpeeches?

LSAMonRepresentByTopics[ aStateOfUnionSpeeches[[ Range[-5, -2] ]] ]?

LSAMonTakeValue;

sMat1 = WeightTermsOfSSparseMatrix[sMat1, "None", "None", "Cosine"]

sMat2 =

lsaSpeeches?

LSAMonRepresentByTopics[ aStateOfUnionSpeeches[[ Range[-7, -3] ]] ]?

LSAMonTakeValue;

sMat2 = WeightTermsOfSSparseMatrix[sMat2, "None", "None", "Cosine"]

MatrixForm[sMat1.Transpose[sMat2]]

Note the differences with the weighted Boolean similarity matrix in the previous sub-section -- the similarities that are less than 1 are noticeably larger.

Unit tests

The development of LSAMon was done with two types of unit tests: (i) directly specified tests, [AAp7], and (ii) tests based on randomly generated pipelines, [AA8].

The unit test package should be further extended in order to provide better coverage of the functionalities and illustrate -- and postulate -- pipeline behavior.

Directly specified tests

Here we run the unit tests file "MonadicLatentSemanticAnalysis-Unit-Tests.wlt", [AAp8].

AbsoluteTiming[

testObject = TestReport["~/MathematicaForPrediction/UnitTests/MonadicLatentSemanticAnalysis-Unit-Tests.wlt"]

]

The natural language derived test ID's should give a fairly good idea of the functionalities covered in [AAp3].

Values[Map[#["TestID"] &, testObject["TestResults"]]]

(* {"LoadPackage", "USASpeechesData", "HamletData", "StopWords",

"Make-document-term-matrix-1", "Make-document-term-matrix-2",

"Apply-term-weights-1", "Apply-term-weights-2", "Topic-extraction-1",

"Topic-extraction-2", "Topic-extraction-3", "Topic-extraction-4",

"Statistical-thesaurus-1", "Topics-representation-1",

"Take-document-term-matrix-1", "Take-weighted-document-term-matrix-1",

"Take-document-term-matrix-2", "Take-weighted-document-term-matrix-2",

"Take-terms-1", "Take-Factors-1", "Take-Factors-2", "Take-Factors-3",

"Take-Factors-4", "Take-StopWords-1", "Take-StemmingRules-1"} *)

Random pipelines tests

Since the monad LSAMon is a DSL it is natural to test it with a large number of randomly generated "sentences" of that DSL. For the LSAMon DSL the sentences are LSAMon pipelines. The package "MonadicLatentSemanticAnalysisRandomPipelinesUnitTests.m", [AAp9], has functions for generation of LSAMon random pipelines and running them as verification tests. A short example follows.

Generate pipelines:

SeedRandom[234]

pipelines = MakeLSAMonRandomPipelines[100];

Length[pipelines]

(* 100 *)

Here is a sample of the generated pipelines:

Here we run the pipelines as unit tests:

AbsoluteTiming[

res = TestRunLSAMonPipelines[pipelines, "Echo" -> False];

]

From the test report results we see that a dozen tests failed with messages, all of the rest passed.

rpTRObj = TestReport[res]

(The message failures, of course, have to be examined -- some bugs were found in that way. Currently the actual test messages are expected.)

Future plans

Dimension reduction extensions

It would be nice to extend the Dimension reduction functionalities of LSAMon to include other algorithms like Independent Component Analysis (ICA), [Wk5]. Ideally with LSAMon we can do comparisons between SVD, NNMF, and ICA like the image de-nosing based comparison explained in [AA8].

Another direction is to utilize Neural Networks for the topic extraction and making of statistical thesauri.

Conversational agent

Since LSAMon is a DSL it can be relatively easily interfaced with a natural language interface.

Here is an example of natural language commands parsed into LSA code using the package [AAp13].

Implementation notes

The implementation methodology of the LSAMon monad packages [AAp3, AAp9] followed the methodology created for the ClCon monad package [AAp10, AA6]. Similarly, this document closely follows the structure and exposition of the `ClCon monad document "A monad for classification workflows", [AA6].

A lot of the functionalities and signatures of LSAMon were designed and programed through considerations of natural language commands specifications given to a specialized conversational agent.

References

Packages

AAp1] Anton Antonov, [State monad code generator Mathematica package, (2017), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub*.

AAp2] Anton Antonov, [Monadic tracing Mathematica package, (2017), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub*.

AAp3] Anton Antonov, [Monadic Latent Semantic Analysis Mathematica package, (2017), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AAp4] Anton Antonov, [Implementation of document-term matrix construction and re-weighting functions in Mathematica, (2013), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AAp5] Anton Antonov, [Non-Negative Matrix Factorization algorithm implementation in Mathematica, (2013), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AAp6] Anton Antonov, [SSparseMatrix Mathematica package, (2018), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AAp7] Anton Antonov, [MathematicaForPrediction utilities, (2014), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AAp8] Anton Antonov, [Monadic Latent Semantic Analysis unit tests, (2019), MathematicaVsR at GitHub.

AAp9] Anton Antonov, [Monadic Latent Semantic Analysis random pipelines Mathematica unit tests, (2019), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AAp10] Anton Antonov, [Monadic contextual classification Mathematica package, (2017), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AAp11] Anton Antonov, [Heatmap plot Mathematica package, (2017), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AAp12] Anton Antonov,

[Independent Component Analysis Mathematica package, MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AAp13] Anton Antonov, [Latent semantic analysis workflows grammar in EBNF, (2018), ConverasationalAgents at GitHub.

MathematicaForPrediction articles

AA1] Anton Antonov, ["Monad code generation and extension", (2017), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AA2] Anton Antonov, ["Topic and thesaurus extraction from a document collection", (2013), MathematicaForPrediction at GitHub.

AA3] Anton Antonov, ["The Great conversation in USA presidential speeches", (2017), MathematicaForPrediction at WordPress.

AA4] Anton Antonov, ["Contingency tables creation examples", (2016), MathematicaForPrediction at WordPress.

AA5] Anton Antonov, ["RSparseMatrix for sparse matrices with named rows and columns", (2015), MathematicaForPrediction at WordPress.

AA6] Anton Antonov, ["A monad for classification workflows", (2018), MathematicaForPrediction at WordPress.

AA7] Anton Antonov, ["Independent component analysis for multidimensional signals", (2016), MathematicaForPrediction at WordPress.

AA8] Anton Antonov, ["Comparison of PCA, NNMF, and ICA over image de-noising", (2016), MathematicaForPrediction at WordPress.

Other

[Wk1] Wikipedia entry, [Monad](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monad_(functional_programming)),

[Wk2] Wikipedia entry, Latent semantic analysis,

[Wk3] Wikipedia entry, Distributional semantics,

[Wk4] Wikipedia entry, Non-negative matrix factorization,

[LE1] Lars Elden, Matrix Methods in Data Mining and Pattern Recognition, 2007, SIAM. ISBN-13: 978-0898716269.

[MB1] Michael W. Berry & Murray Browne, Understanding Search Engines: Mathematical Modeling and Text Retrieval, 2nd. ed., 2005, SIAM. ISBN-13: 978-0898715811.

[MS1] Magnus Sahlgren, "The Distributional Hypothesis", (2008), Rivista di Linguistica. 20 (1): 33[Dash]53.

[PS1] Patrick Scheibe, Mathematica (Wolfram Language) support for IntelliJ IDEA, (2013-2018), Mathematica-IntelliJ-Plugin at GitHub.