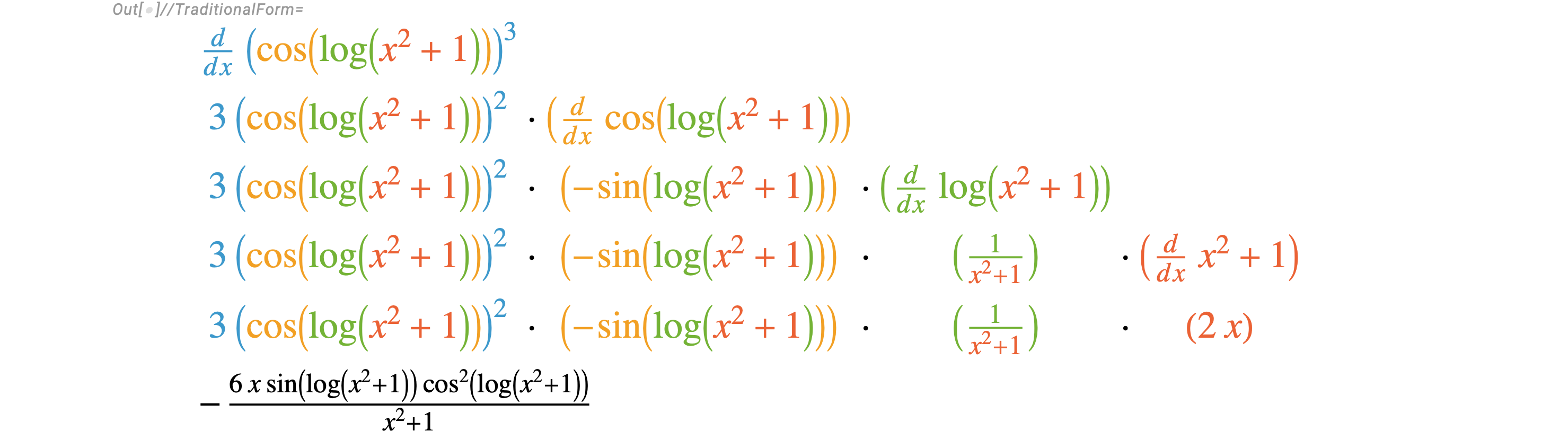

Here's a representation of how I show my students. It's for strictly composite formulas, by which I mean functions of the form

$f\circ g \circ \cdots \circ h$ or as a formula

$f(g(\cdots h(x)))$. It won't deal with a formula like the following:

$$f\left(g\bigl(h(k(l(x)))\cdot m(n(x)+p(q(r(x))))\bigr)\right) \tag{1}$$

The extreme elaborateness of

$(1)$ is just to drive home why I wouldn't consider going "inside-out" with the chain rule. I suppose it's clear enough what to do on

$\ln(\cos(e^x))$, but when the inside components involve combinations of sums, products, quotients, and compositions such as

$\ln(\cos(x^2)+\sin(e^{3x})$, where do you start on the inside? At

$x^2$ or

$3x$? Or do you start in the middle with

$\cos(x^2)+\sin(e^{3x}$ and work your way both up and down? How in the world could I ever explain the process to a group of students?

But mainly I go "outside-in", because that's how I was taught and that's all I have ever done. My first year in college in 1981, I was introduced to computational symbolic algebra in first-year math (via LISP). A couple of years later, I learned to write parsers, and I wrote a small CAS for fun. Programming the chain rule seemed natural to go outside-in. Yet another reason is that when you start substitution in integrals, the first examples generally involve substitutions where one lets

$u$ be the inside of the outermost function of one the factors. Thus outside-in is a way to quickly identify probable substitutions. If one goes inside-out, several consecutive substitutions might be needed.

Finally, one calculus book I once used wrote the chain rule in a hybrid Leibniz way,

$d(f(u)) = f'(u) \; du$, and the derivative rules for all the particular functions in the corresponding differential form like this:

$d(\cos u)=(-\sin u) \; du$, etc. At the end of the process, you divide by

$dx$ or whatever to get the derivative. It was meant to be used outside-in as follows:

$${

d(\ln(\cos e^x))

={1\over \cos e^x}\cdot d(\cos e^x)

={1\over \cos e^x}(-\sin e^x) \cdot d(e^x)

={-\sin e^x\over \cos e^x} e^x \;dx

}$$

Then divide by

$dx$.

In any case, I usually teach it outside-in with the derivative operator

$d/dx$ instead of the differential operator as follows:

Of course, I don't write such colors on the board in class. (I usually underline the inside part to be differentiated on the outside per the chain rule, as a way to highlight it.)

Code dump

Fancy formatting needs fancy code unfortunately.

ClearAll[dt, dd, pow, exp, pp];

(* Univariate forms of Power[] *)

pow[k_]'[x_] :=

If[k == 2, 2 x, k*pow[k - 1][x]]; (* power functions #^k& *)

exp[k_]'[x_] := Log[k]*exp[k][x]; (* exponential functions k^#& *)

toUnivariatePower = {sum_Plus :> sum, term_Times :> term,

Power[a_, b_] /; ! FreeQ[a, x] :> pow[b][a],

Power[a_, b_] /; ! FreeQ[b, x] :> exp[a][b]};

fromUnivariatePower = {pow[b_][a_] :> Power[a, b],

exp[a_][b_] :> Power[a, b]};

MakeBoxes[pow[k_][x_], form_] :=

SuperscriptBox[RowBox[{"(", MakeBoxes[x, form], ")"}],

MakeBoxes[k, form]];

MakeBoxes[exp[k_][x_], form_] := MakeBoxes[Power[k, x], form];

(* Extra parentheses and the derivative operator (for output display) *)

MakeBoxes[pp[y : _. pow[_][_]], form_] :=(* don't parenthesize *)

MakeBoxes[y, form];

MakeBoxes[pp[y_], form_] :=(* parenthesize *)

RowBox[{"(", MakeBoxes[y, form], ")"}];

MakeBoxes[dd[y_], form_] :=(* derivative operator *)

RowBox[{ (* choose "d" or "\[PartialD]" *)

FractionBox["d", "d\[InvisibleSpace]x"],

MakeBoxes[y, form]}];

dt[f_[x_], "Style", n_] :=

Style[f[dt[x, "Style", n + 1]], ColorData[116][n]];

dt[y_, "Style", n_] := Style[y, ColorData[116][n]];

dt[y_] := TraditionalForm@Grid[

Replace[

Rest /@ dt[dt[murf = y //. toUnivariatePower, "Style", 1], {}]

, row_List /; Length@row > 1 && FreeQ[row, SpanFromLeft] :>

Replace[row, Style[x_, s_] :> Style[pp@x, s], 1], 1]

, Alignment -> Automatic, Spacings -> {0, Automatic}];

dt[sf : Style[f_[x_], s__],

pre_] := {{Sequence @@ pre, " \[CenterDot] ", Style[dd[f[x]], s]},

Sequence @@ dt[x, Join[pre, {" \[CenterDot] ", Style[f'[x], s]}]]};

dt[sy : Style[y_, s__],

pre_] := {{Sequence @@ pre, " \[CenterDot] ", Style[dd[y], s]},

Sequence @@ dt[x, Join[pre, {"\[CenterDot]", Style[D[y, x], s]}]]};

dt[x, pre_] := {pre, {Null,

Item[Times @@ pre[[2 ;; ;; 2]] /.

RawBoxes -> (ReleaseHold@

MakeExpression[#, TraditionalForm] &) /.

Style -> (# &) //. fromUnivariatePower, Alignment -> Left],

SpanFromLeft}};

(* Example shown above: *)

dt[Cos[Log[x^2 + 1]]^3]