I would like to weigh in here even though I'm not an academic, because it's a topic dear to my heart. I think the most valid complaint on Craig's list is number 2. Here's the test: How much time is spent in doing the math and science and how much time in trying to coerce Mathematica into doing what you want? If it tilts too much to the latter Mathematica will lose.

Nevertheless, Mathematica has tremendous advantages, which many academics and users seem to be unaware of and which are basically out-of-sight. It could and should be the premiere publication medium for technical (and maybe even a lot of non-technical) material. It should blow LaTex and PDF documents out of the water. This is because of the active and dynamic capabilities of Mathematica notebooks (and CDF documents): the ability to transmit usable routines with the documents, and the ability to accumulate capability in a documented form, not to speak of all the capability built into Mathematica itself.

And yet, Mathematica has completely failed at this. Look at arXiv.org. How many Mathematica notebooks will you find? I haven't tried to check or search all entries but it looks like the score is something like LaTex/PDF 1,000,000, Mathematica notebooks 0. (Of course, some of the PDF's have graphics or mathematical results copied from Mathematica.) So how many academics even see examples of what can be done?

Academics need a positive reason to switch to Mathematica for routine work. There are plenty of very good reasons. They just don't see them.

On the other hand, the second item on Craig's list is quite important. Mathematica is difficult to use. Wolfram Research has not made sufficient effort in usability. Their approach has been to add more bells and whistles and top-down routines. This only makes usage more difficult. Often you may find that you have to modify a high level routine, generally using options or special constructions, to get what you want - only to find out after several hours that it can't be done. It would be much simpler if, as much as possible, capability was built from the bottom up and made available to the user. It's all right to offer some common high level routines (built from the lower level objects) but the user should always have the option to fall back to the more primitive constructions.

For graphics and dynamic displays, the paradigm should be "writing on a piece of paper". That's what academics do all the time. They kind of understand that. In part, that means separating the calculation from the writing.

Another difficulty is that this active and dynamic medium is quite new and revolutionary. Even if Mathematica were easy to use, it's still not all that clear or simple to know the best usage. It's easy to fill displays with "computer junk". Just taking a 19th or 20th century diagram and making something move is not necessarily very informative. There are many possibilities and matters of taste that need to be creatively explored. This is why WRI has to leave the user free to write displays adapted to special cases at hand. They can't even come close to anticipating what form these might take - or providing high level routines for them.

Finally, I would like to include two display examples, which Mathematica's high level routines are not particularly good at doing. I didn't use standard methods for either of these and yet they should be the kind of thing that would be reasonably easy to do,

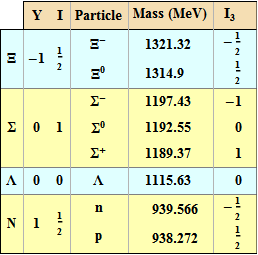

The following is adapted from the first table I found in Arfken & Weber, Mathematical Methods for Physics, Fifth Edition, 2001, Academic Press. The original was somewhat confusing. This was composed using a set of routines that allow me to write information and formatting directly on a "piece of paper" without using the rather complicate options in Grid. Would you find it easy to compose this using Grid? Does technical work ever use custom tables?

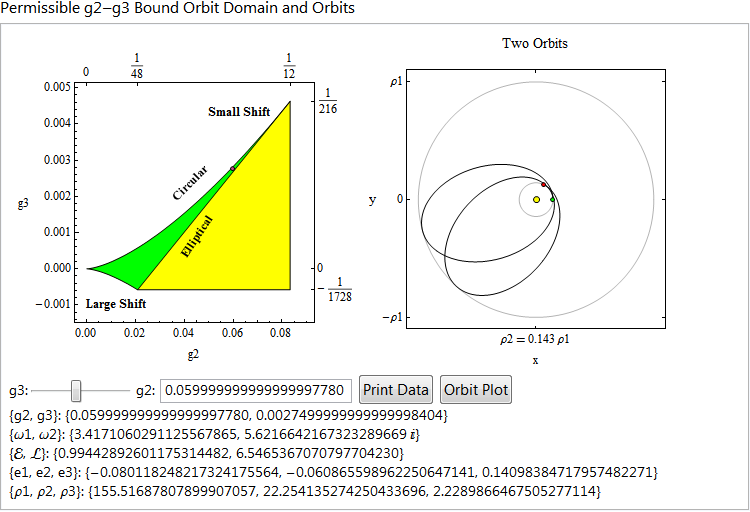

The second example is from a notebook on the use of the Weierstrass elliptic P function in representing EXACT solutions of orbits in the Schwarzschild geometry. I was introduced to this by Ron Burns. This was done using a DynamicModule. I never use the Manipulate statement. I find it too difficult to con out its behavior and I want to arrange the layout just the way I want. The Weierstrass function is characterized by two parameters, g2 and g3, and the green region shows the domain for bound orbits. The region is a thin wedge where most of the physical cases occur. The g3 Slider is dynamically adapted to this and varies only across the green domain - the variation is in the 5th or 6th place. Even though the Weierstrass function was known well before Einstein and Schwarzschild, not to speak of Misner, Thorn and Wheeler, the high precision required probably mitigated against its use. But you can see that I used quite high precision and Mathematica had no difficulty with it at all. That might be one powerful reason in favor of Mathematica.